Many have celebrated Mother’s Day throughout the years, but seldom, if ever, do we give thought to how the holiday started. Some claim it was secretly invented by Hallmark as a way to sell greeting cards.

As it turns out, the truth is far more intriguing… especially for those of us who are committed to the health of our families and our communities.

Mothers and motherhood have been celebrated in many different ways by many different cultures across the centuries. The modern version of Mother’s Day, however, began in the United States just over a century ago.

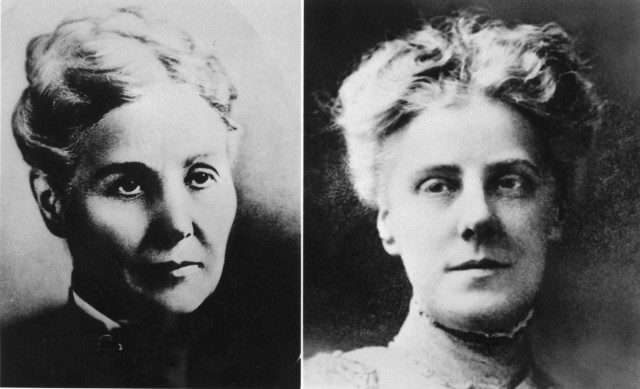

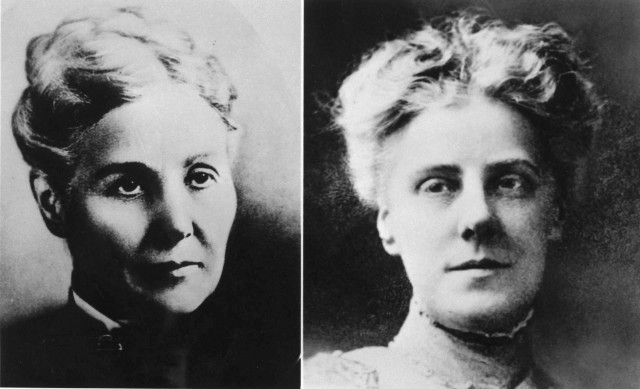

Ann Marie Reeves (left) and her daughter Anna Marie Jarvis (right)

Ann Marie Reeves (left) and her daughter Anna Marie Jarvis (right)

Local observances, often led by reformers from the temperance and abolitionist movements, were held during the 1870s and the 1880s. However, the national celebration that we now know as Mother’s Day came about thanks to the concentrated efforts of Anna Jarvis. In May of 1908, Anna Marie Jarvis held a memorial for her own mother in Grafton, West Virginia. She went on to launch a national and international campaign to make the day a formally recognized holiday. In 1914, Woodrow Wilson signed a proclamation naming the second Sunday in May a national holiday: Mother’s Day.

Anna’s desire was to celebrate her own mother’s legacy and encourage all Americans to set aside a day to celebrate and honor “the person who has done more for you than anyone in the world.”1 And, I have to say, Anna had plenty of reasons to celebrate her mother’s life and legacy.

Anna’s mother, Ann Marie Reeves, was the daughter of a Methodist minister. In 1850, she married Granville Jarvis, the son of a Baptist minister. The couple moved to the Appalachian mountains of Western Virginia where Ann Marie gave birth to twelve children. Sadly, due to the recurrent epidemics of typhoid, measles and diphtheria that swept through the Appalachian communities, only four of her children survived to adulthood.

Ann Marie Reeves, however, was a natural activist. Her personal grief at losing so many of her children in infancy inspired her to become a determined crusader for public health. As early as 1858, Ann Marie was working in her own community and surrounding communities to organize Mother’s Day Work Clubs.

Mother’s Day Work Clubs, which were based in local churches of all denominations, brought together women in the church community to work together for the greater public. The clubs worked diligently to improve the health and sanitary conditions in their communities.

Club members would visit local families to provide information and education on sanitation, nutrition and overall health. The clubs also raised money to help families who needed assistance covering medical costs. These women even worked together to provide household help for mothers suffering from tuberculosis and other illnesses.2

During the Civil War, the mission of the Mother’s Day Work Clubs evolved, as members turned their efforts to caring for the many soldiers wounded in the fighting that raged across the mountains during the first years of the war. Tensions were particularly high in the Appalachian mountains of Western Virginia, as communities and even families were divided in their support for either the Union or the Confederacy.

Ann Marie’s leadership was an important part of the decision of the Mother’s Day Work Clubs to remain neutral during the conflict, despite significant pressure to take sides. Local Mother’s Day Work Clubs provided food and clothing to soldiers from both sides that were stationed in the area. These local women nursed soldiers in the military camps of both armies when outbreaks of typhoid fever and measles swept through the camps.

Even after the Civil War ended, the clubs continued to take an active part in promoting peace and reconciliation in their war-torn communities. In 1868, despite threats of violence, club members held a Mother’s Day of Friendship for veterans from both sides of the conflict.3 The women arranged for the band to play first the confederate ballad “Dixie,” then the Union’s “Star Spangled Banner” and ended with the entire community joining together to sing “Auld Lang Syne.”

Given her mother’s incredible work, I’m hardly surprised that Anna decided it was important to publicly celebrate the incredible women who have cared, nurtured and inspired us. What does surprise me is that I’d never heard the story of this incredible woman.

In the 100 years since Anna began working to make Mother’s Day a national holiday the holiday has changed – and in ways that Anna herself didn’t appreciate. Anna had envisioned mother’s day as a time to recognize and celebrate the incredible work that mothers do – both in caring for their own children but also caring for the community at large. She was extremely upset at how the holiday was co-opted by candy and greeting card companies. In 1923, she even crashed a candy-makers’ convention in Philadelphia to protest the commercialization of the holiday she had started.4

Mother’s Day may be over-commercialized, much to Anna Jarvis’s chagrin, but it’s still kind and thoughtful to send your mother a loving message or give her the gift of health to show your love and appreciation on her special day.

References

1 Lois M. Collins, “Mother’s Day’s 100-year history: a colorful tale of love, anger and civic unrest,” Desecret News, 6 May 2014.

2 Howard H. Wolfe, Mother’s Day and the Mother’s Day Church (Kingsport, TN: Kingsport Press, 1962).

3 Katherine Lane Antolini, Memorializing Motherhood: Anna Jarvis and the Struggle for Control of Mother’s Day” (PhD diss.,

West Virginia University, 2009

4 Time Engle, “Hallmark celebrates 100th year of Mother’s Day, started by a woman who grew to despise it,” The Wichita Eagle, 27 April 2014.

Join Over 200,000 Gerson Fans

![]() Educational articles like this are made possible with the help of your donations. Help us continue the legacy of Dr. Max Gerson, his daughter Charlotte Gerson, and the thousands who rely on the Gerson Institute for vital educational materials and training.

Educational articles like this are made possible with the help of your donations. Help us continue the legacy of Dr. Max Gerson, his daughter Charlotte Gerson, and the thousands who rely on the Gerson Institute for vital educational materials and training.

Originally Published May 2015