Jessica Luibrand, BS, CCT (Certified Clinical THermographer)

For years, new research has called into question the effectiveness of mammography. As a result, the American Cancer Society (ACS) changed their stance on mammograms in October 2015. ACS previously recommended that annual mammograms begin at 40 years of age. But now with increased knowledge of the limitations and potential harms of mammography, the ACS recommends that annual screening shouldn’t start until age 45 and should change to every two years starting at 55¹.

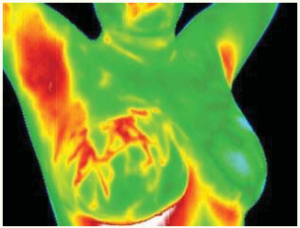

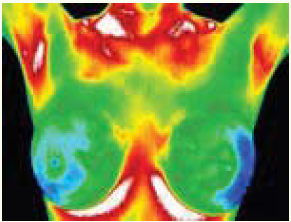

Thermography is a non-invasive way to study the physiology of the human body (as differentiated from ultrasound and mammograms, which study the structure of the body). Thermography simply detects subtle variations in skin temperature using an infrared camera in a temperature-controlled room, which can provide clues to what is going on beneath the surface of the skin. Humans are infrared beings and they give off energy in the form of heat. An infrared camera (think night-vision) is heat-sensitive. Whereas a mammogram emits ionizing radiation through your compressed breast tissue, on a thermogram you radiate your energy toward the camera. Thus, nothing is passed through your body. Another very common example of using heat to detect illness is getting your temperature checked at a doctor’s visit because fever (excess heat) implies infection or dis-ease.

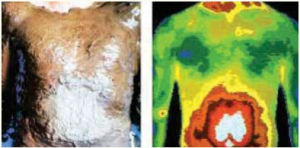

Left: A slurry of wet clay on a patient the way Hippocrates would have used it, quickly dried around the umbilicus (belly button) indicating excess heat.

Right: Thermogram showing excess heat in the exact same area around the umbilicus.

Hippocrates is considered the “father of modern medicine” as we know it. You may have heard of the Hippocratic Oath that present-day doctors still take, promising to “do no harm”. Something less well-known is that Hippocrates is also the “father of thermography.” In 400 AD, Hippocrates smeared wet clay over his patients’ bodies looking for patterns in the clay as it dried. He noticed that some areas dried more quickly than others, because of excess internal heat. He is quoted as saying “in whatever part of the body excess heat or cold is felt, there is disease to be discovered.”²

Cancer is fed by the body’s own blood supply. Thermography can detect the increased heat that results from the early development of vascularity (angiogenesis) to feed the cancer. When cancer occurs in our body the normal cell-death mechanism (called apoptosis or regulated cell death) turns off. The cell “forgets” to die and continues growing, untamed and unchecked.³ Because this process begins on a cellular level, no solid mass forms right away, only a small gathering of cells. Only after growing for a certain number of years does a cancerous tumor become large enough to finally be seen on a mammogram.

The chart below was developed from Dr. Michael Retsky’s cancer-growth research showing that the possible observation times for a mammogram to find a tumor are near the end of the tumor’s growth, which does not constitute early detection. His research found that breast cancer typically doubles in volume in about 100 days. Since mammography is usually able to find breast tumors at approximately 1 cm, he estimates the usual time to detect breast cancer is at 30 doublings (of 100 days each)-a total of 8 years. He concludes that “the possible observation times in breast cancer is limited to between the 30th and 40th doublings or at most the last 25% of the growth history of a tumor.”4

90 days

1 year

2 years

3 years

5 years

6 years

7 years

8 years

2 cells

16 cells

256 cells

4, 896 cells

1,048,576 cells

16,772,216 cells

268,435,456 cells

4,294,967,296 cells

Mammography

Mammograms were called into question because of their large number of false positives, as well as the issue of overdiagnosis and overtreatment. If mammograms were truly helping diagnose cancer early they should improve overall breast cancer mortality rates-but there are some studies indicating that they don’t.5 Most often breast cancers are found in the upper outer area of the breasts, in between the breast tissue and the armpit6 which cannot be visualized on a mammogram.

Mammograms have an average sensitivity of 80% in women over 50, which drops to 60% in women under 507. Hormone usage decreases the sensitivity of mammograms. In addition, since mammograms are not able to differentiate between a solid tumor and fluid-filled cyst or calcification, women who have scar tissue or dense or fibrocystic breasts have a tendency to get called back to have a repeat mammogram (resulting in more radiation exposure) because of difficulties reading the scans. In spite of all of this, there is a strong commitment by the National Cancer Institute to reassure women that the benefits of mammography outweigh the risks. But repeated X-ray exposure can cause cancer.8

Thermography

Thermography is a reasonable alternative for women who want to avoid the radiation exposure from a mammogram, for those who have implants (since it does not damage them) or for women who have had other breast surgeries resulting in scar tissue. It is also a great option for women who are considered high risk, are taking hormones, are younger or have dense breasts. Additionally, thermography has no harmful side effects so it can be used as often as desired.

According to the American College of Clinical Thermography, thermography can detect abnormalities of the female breast and can also examine breast tissue in men. Another advantage is that the entire chest is observed (neck to abdomen and armpit to armpit) and there is no compression of tissue, which can sometimes spread cancer cells.9 Thermography can also monitor treatment effectiveness and can distinguish between benign and malignant tissue in women with fibrocystic breasts.

“Thermography offers a safe, noninvasive procedure that would be valuable as an adjunct to mammography”

There are over 800 peer-reviewed articles supporting the effectiveness of thermography10 and there are many well-known supporters of thermography including Dr. Christiane Northrup, Dr. Joseph Mercola and Dr. Veronique Desaulniers. Thermography was also most recently featured in Episode 2 of The Truth About Cancer (an online documentary series). Thermography was even approved by the FDA as an adjunctive test to mammography in 1982.

A 2003 study indicated “Thermography offers a safe, noninvasive procedure that would be valuable as an adjunct to mammography in determining whether a lesion is benign or malignant with a 99% predictive value”.11

A 2003 study indicated “Thermography offers a safe, noninvasive procedure that would be valuable as an adjunct to mammography in determining whether a lesion is benign or malignant with a 99% predictive value”.11

A study published in 2008 by The American Society of Breast Surgeons concluded that DITI (digital infrared thermal imaging, or thermography) was a valuable adjunct to mammography and ultrasound especially in women with dense breast parenchyma [tissue] because of its 97% sensitivity.12

The American College of Clinical Thermography also describes the benefit of doing thermography along with mammography, citing the results of Canadian research showing the sensitivity rate of mammography alone was increased to 95% when infrared imaging was added.13

In 2013, researchers Kolaric et. al. found thermography to have the probability of a correct finding in 92% of cases. They concluded that “breast cancer remains the most prevalent cancer in women and thermography exhibited superior sensitivity. We believe that thermography should immediately find its place in the screening programs for early detection of breast carcinoma, in order to reduce the sufferings from this devastating disease.”14

According to women’s health specialist, Dr. Christine Horner, thermography can “detect breast cancers much earlier than any other available technology. Because blood vessels ordinarily start to grow before any other significant changes and tumor growth, a thermogram can ‘see’ these abnormal physiological processes as early as 5-10 years before a cancer can be seen by a mammogram, MRI, or ultrasound or felt by a physical exam. What is most exciting is that when these abnormal processes are caught this early they are reversible.”15 This gives time for natural interventions such as diet, supplementation and lifestyle changes like stress management to heal the body.

Editor’s note: According to the American College of Clinical Thermography (ACCT), “One day there may be a single method for the early detection of breast cancer. Until then, using a combination of methods will increase your chances of detecting cancer in an early state.”16 The ACCT suggests an annual thermography screening, mammography when appropriate, and regular breast exams.

The ACCT explains that most women use thermography in addition to mammography and/or ultrasound. They believe thermal imaging should be “viewed as a complementary, not competitive, tool to mammography and ultrasound” that can increase the effectiveness of those two structural tests by identifying patients having the highest risk level.17

The International Academy of Clinical Thermography says that thermography is not a replacement for mammography because “there is no one test that can detect 99-100% of all cancers.” In addition, thermography and mammography “are ‘looking’ for completely different pathological processes” because one tests physiology and the other tests anatomy. Lastly, they explain that “thermography is far more sensitive than mammography; however, some slow growing non-aggressive cancers will only be detected by mammography.”18

Breast cancer detection is multifaceted issue that requires an individualized approach. Each person must make their own decision and stay aware of the most current research. Mammography and thermography can be beneficial detection tools, depending on the circumstances. Use of one or the other, or both, depends on a variety of factors, such as age, history of disease, disease status, type of cancer, density of breast tissue and more. Remember that thermography or mammograms or breast exams cannot diagnose cancer. If something suspicious is found on a mammogram, or by ultrasound, breast exam or thermography, the definitive diagnosis can only be done by biopsy.

Written by: Jessica Luibrand, BS, CCT (Certified Clinical Thermographer)

Jessica Luibrand attended Grand Valley State University where she received her Bachelor’s degree in Health Sciences with a double major in Biology and Sociology. She is currently employed as Chief Clinical Thermographer and Subtle Energy Researcher at Psy-Tek Subtle Energy Laboratory. Her mission is to combine her love of health and wellness with her love of people.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue of Healing News.

![]() Educational articles like this are made possible with the help of your donations. Help us continue the legacy of Dr. Max Gerson, his daughter Charlotte Gerson, and the thousands who rely on the Gerson Institute for vital educational materials and training.

Educational articles like this are made possible with the help of your donations. Help us continue the legacy of Dr. Max Gerson, his daughter Charlotte Gerson, and the thousands who rely on the Gerson Institute for vital educational materials and training.

Sources

- “American Cancer Society Releases New Breast Cancer Guideline,” American Cancer Society, accessed February 20, 2016, http://www.cancer.org/cancer/news/news/american-cancer-society-releases-new-breast-cancer-guidelines.

- “Aphorisms by Hippocrates,” The Internet Classics Archives, accessed February 21, 2016, http://classics.mit.edu/Hippocrates/aphorisms.4.iv.html.

- Rebecca SY Wong, “Apoptosis in cancer: from pathogenesis to treatment,” Journal of Experimental and Clinical Cancer Research, 30(1) (2011): 87.

- “M. Retsky, PhD. Cancer Growth Implication for Medicine and Malpractice White Paper,” Technical Assistance Bureau, accessed February 21, 2016, http://www.lectlaw.com/filesh/tabtumo.htm.

- “Screening for Breast Cancer with Mammography,” Cochrane, accessed February 21, 2016, http://www.cochrane.org/CD001877/BREASTCA_screening-for-breast-cancer-with-mammography.

- AH Lee, “Why is carcinoma of the breast more frequent in the upper outer quadrant? A case series based on needle core biopsy diagnoses,” Breast, 14(2) (2005): 151-2.

- “Accuracy of Mammograms,” Susan G. Koman, accessed February 21, 2016, http://ww5.komen.org/BreastCancer/AccuracyofMammograms.html.

- “Mammograms Fact Sheet,” National Cancer Institute, accessed February 21, 2016, http://www.cancer.gov/types/breast/mammograms-fact-sheet.

- Johannes P. van Netten, Stephen A. Cann and James G. Hall, “Mammography Controversies: Time for Informed Consent? “Oxford Medicine & Health: Journal of National Cancer Institute, 89 (15) (1997): 1164-1165.

- “Breast Screening Questions and Answers,” American College of Clinical Thermography, accessed February 21, 2016, http://www.thermologyonline.org/Breast/breast_q_a/bqa_clinicaltests.htm.

- R. Parisky, A. Sardi, R. Hamm, K. Hughes, L. Esserman, S. Rust and K.Callahan, “Efficacy of Computerized Infrared Imaging Analysis to Evaluate Mammographically Suspicious Lesions.” American Journal of Roentgenolgy 180 (January 2003).

- Arora, “Effectiveness of a Noninvasive Digital Infrared Thermal Imaging System in the Detection of Breast Cancer,” The American Journal of Surgery (October 1, 2008): 523-26.

- “Breast Screening Questions and Answers,” American College of Clinical Thermography, accessed February 21, 2016, http://www.thermologyonline.org/Breast/breast_q_a/bqa_accurate.htm.

- Kolaric et al. “Thermography- A Feasible Method for Breast Cancer Screening?” Collegium Anthropologicum 37 (2013): 583-588.

- Christine Horner, Waking the Warrior Goddess: Dr. Christine Horner’s Program to Protect Against and Fight Breast Cancer, (New Jersey: Basic Health Publications, 2005), 21.

- “Early Detection Guidelines,” American College of Clinical Thermography, accessed February 21, 2016, http://www.thermologyonline.org/Breast/breast_thermography_detection.htm.

- “Mammography vs. Thermography,” International Academy of Clinical Thermography, accessed February 21, 2016, http://www.iact-rg.org/patients/breastthermography/mammography-vs-therm.html.

- “Breast Screening Questions and Answers,” American College of Clinical Thermography, accessed February 21, 2016, http://www.thermologyonline.org/Breast/breast_q_a/bqa_replacement.htm.