I spent a good part of my career as a journalist, covering news stories in the Middle East. I reported on the Iraq war, the withdrawal from Gaza, the war in Lebanon, Ahmedinejad’s rise to power in Iran, the election win of Hamas in the Palestinian territories, and many other intense events. So you might ask yourself how I suddenly got the idea to do a documentary about people undergoing a nutritional cancer therapy.

It began after a tiring stint in Lebanon. I got back to the US feeling that I wanted to do something really different for a while; something lighter and easier. I needed a break: from war, from hardship, from the pain in people’s eyes.

Food as Medicine?

Listening to the radio in NYC one day, I heard a quote from Charlotte Gerson in which she claimed that a ‘cure for cancer’ had been found many years ago.

Obviously, I knew for a fact that this wasn’t true, and this outrageous statement made me furious.

Two of my closest friends are oncologists. Not only do I deeply admire their brilliance and incredible dedication, I have personally witnessed their suffering each and every time they lose a patient.

Despite the extraordinary advances in technology and drug research; despite the great scientific minds and the billions of dollars that have been thrown at this problem in the last century, today my friends still can’t save many of their patients.

So I jotted down the ludicrous statement and began researching what this loudmouthed elderly lady was referring to. A magazine showed interest in my proposal to do a story about alternative cancer clinics in Mexico that are preying on desperate cancer patients at the most vulnerable moment in their lives. Granted, it wasn’t much more lighthearted than the war work, but I felt that it was important.

After all, senseless dying isn’t only happening in far-away places like the Middle East – there is a quieter sort of mass death going on right here, on our own doorstep, and I knew some of its victims personally.

When I began getting deeper into my research, I was surprised that the man behind the Gerson Therapy was not – as I had assumed – some pseudo-doctor or crazed small-time country doc, but rather a bona fide medical doctor with an illustrious career, considered brilliant by many of his peers. Albert Schweitzer had even called him “the most eminent genius in medical history.”

Intrigued and with the advantage of speaking German, I dug up old German medical journals and press articles about his work. There was a major study applying his unusual dietary therapy to patients with skin tuberculosis, then an incurable disease. Professor Ferdinand Sauerbruch, now considered the father of thoracic surgery, had conducted a widely publicized and carefully monitored clinical trial on 450 end-stage tuberculosis patients, with the astonishing result that 446 of them made full recoveries.

The Investigation Begins

The story was becoming more and more intriguing, so I contacted the Gerson Institute in San Diego and scheduled a meeting with their executive director, Anita Wilson.

I expected to be met with a smile and a set of prepared answers, and then be diplomatically brushed away, which is the way things like this usually go. Nobody really wants a journalist snooping around, much less when one is promoting a controversial alternative cancer therapy.

But Anita seemed genuinely happy that a journalist was taking such interest in their work and gave me access to everything I requested: current patients, former patients, the Institute’s records, the Gerson family’s personal archives, and doctors applying the therapy in Hungary, Romania, and Mexico. They didn’t even try to stop me from contacting disgruntled former employees or patients for whom the therapy had failed.

By this time I was convinced that there was more to this than the typical “quacks trying to steal patients’ money” story. I couldn’t help thinking that if they had something to hide, they wouldn’t allow me to be snooping around like this. Heck, they were being more welcoming and transparent than most government agencies I’ve ever dealt with as a journalist. I went away with the feeling that regardless whether the therapy could actually cure cancer or not, at least these people were genuinely convinced of it.

Most of the conventional doctors and researchers I interviewed afterwards shrugged off the Gerson Therapy with a laugh. “Of course you can’t heal cancer with carrots and enemas. If eating carrots could cure cancer, we would have noticed.” (Editor’s note: Of course, the Gerson Therapy involves much, much more than just carrots and enemas)

A Radical Idea for a Radical Choice

Given the lack of statistics to back up the arguments on either side, I decided to concentrate on the people for whom the outcome of the therapy mattered the most: the patients. Since this therapy takes 2-3 years, it would be difficult to get any real sense of what it is like to undergo it in just the few weeks I had to do the magazine article. So, I gave up the idea of the article.

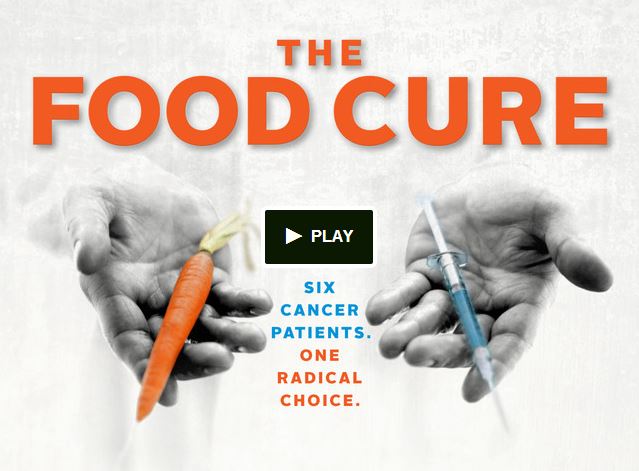

Instead, I decided to find patients who would let me follow them from the beginning until the end of their therapy–WITH A CAMERA. It was the beginning of a long journey to produce the documentary film The Food Cure.

The Food Cure is a feature-length documentary. It follows the stories of six ordinary people who make a radical choice to follow the Gerson Therapy, in the face of a devastating diagnosis. The Food Cure presents a rare and intimate look at the world of alternative cancer therapies and asks big-picture questions about food, health and the future of cancer treatment.

About the Author

Sarah Mabrouk holds Master’s degrees in film and in journalism and has worked as a reporter and camerawoman, most notably in the Middle East, for a number of print, radio, and TV news organizations including AP, BBC, CNN, ABC, NBC, FRANCE24, Eenvandag, and ZDF. THE FOOD CURE is her first feature-length documentary.